On Truth, Politics and Authenticity: Culture in Beleaguered Times

By Catriona Helen Moncrieff Kelly, University of Oxford

The following Presidential Address was given on November 21, 2015 at the 47th Annual ASEEES Convention. Please click through for additional content and here for the original text and resources.

It is a great honour to give this address, and also a significant responsibility. Thank you all for allowing me the floor, and for your generosity in electing me to a position in which I have learned an enormous amount, and benefited from great collegiality, both inside the Board and beyond.

Andy Byford’s thought-provoking study of self-definition among Russian literary historians in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries includes an extensive treatment of ritual occasions such as inaugural lectures. Presidential addresses evidently belong to this category also, and mine will take the usual form of reflections on the field and my own place in it. Alongside this, though, I will also give attention to the announced theme for the 2015 Convention, “Fact”, which attracted well over 50 specialist panels of very high quality (and many more at which some or most papers directly or indirectly addressed the theme). It was also the subject of an excellent Presidential Plenary, and figured in our second Presidential Plenary on Ukraine, notably in the remarks by Andrew Wilson.

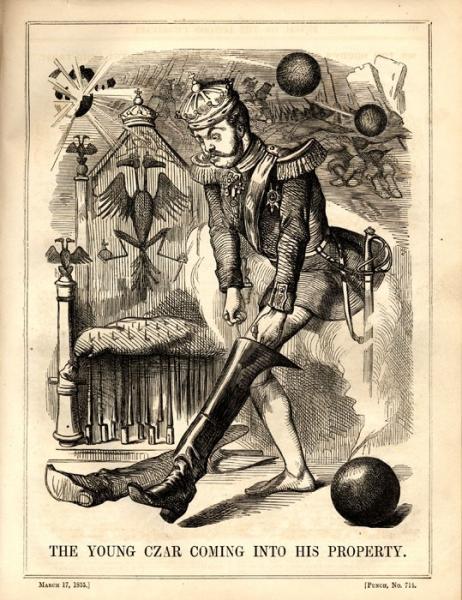

So far as our particular association, and my role in it, goes, the start of my presidential year definitely felt like “beleaguered times”. I was reminded, 160 years after the fact, of a cartoon by John Tenniel. First published on March 17, 1855, it shows the young Alexander II suddenly precipitated into a more exposed position than he had expected.

Of course, an elected figure serving a statutory term has scant resemblance to someone for whom governance is a life sentence, no matter how little they may relish it. Just so, the difference of opinion that broke out in ASEEES earlier this year was not, fortunately, a two and a half-year war fought for little cause and with substantial loss of life; it was an important debate on points of principle, with fierceness only in the rhetoric. It has made our Association stronger, as examination of principles and procedures always does.

In fact, for me, the strongest autobiographical resonance in Tenniel’s cartoon is a very different one. It was one of the most memorable images in the nineteenth-century history textbook that was used for the public examinations sat in the tenth year of high school, Ordinary Levels. A study of British school history books led by David Cannadine not long ago concluded dismissively that the textbooks of the day had few illustrations and was generally pretty stolid and dull. That doesn’t accord with my recollection; I can still remember several of the pictures in the book forty years on, and I recall the text as reasonably interesting too, not just for its word-pictures (London dockers demonstrating with fish-heads and so on), but for its markedly ironic attitude to British imperial adventures and gun-boat diplomacy.

Be that as it may, compared with the often grotesque images of Russia in the Western press at the time, and in the Russian press of Westerners, Tenniel’s drawing is a human and sympathetic glimpse of what was, at the time, the “other side”.

Tenniel’s image of Bismarck, “Dropping the Pilot”, showed equal and commendable restraint. Apparently, Bismarck himself was delighted with the image when Tenniel had him sent a presentation copy.

Tenniel was not just a journeyman cartoonist, but a considerable artist, and in both these pictures he captures effective fictions, mini-narratives: the young ruler who has just entered into his role, and the elder statesmen who is being released from his. Alternatively, one can see it as the typical start and end of a career in any modern society: from overwhelmed and isolated to serenely competent – yet no longer needed. Certainly, there is metaphorical universalism in the pictures: of course we don’t think that Alexander II actually had cannon-balls ricocheting through his throne-room, or that Bismarck spent his retirement messing round in boats. But the details of the setting domesticate world leaders – awe, as well as hostility, is kept distant by familiarity.

My extraction of these images is not purely adventitious. Several analytical themes that have resonated in my academic work can be extrapolated from them. One is the importance of childhood experience, and the difficulty of getting at that experience, and the ways in which it echoes in adult subjectivity — or on the other hand, does not. Felipe Fernandez Armesto, in Truth, suggests that all cultures lose the insights of childhood, but lose them in different ways. One insight that modern academic culture has lost is a sense of any connection with childhood – which seems particularly strange when the perceptions and practices conveniently, if controversially, grouped as “identity” have been so extensively explored. Perhaps the explanation is that academic investigation is inseparable from education, and is preoccupied with hastening the maturation of thought and purifying it from any vestige of the unprofessional and half-baked. To analyse human experience up to the age of 13-14 is, generally speaking, to be intellectually invisible, to be the participant in any general collection of articles who is dismissed in three lines by reviewers as addressing “children’s experience”. Childhood, despite the efforts of specialists such as Margaret Peacock, Marina Balina, Larisa Rudova, Olga Kucherenko, Andy Byford, or, outside our field, Aaron Moore, Colin Heywood, or Nicholas Stargardt, exists on the margins of scholarly investigation. It excites wider interest, if at all, only when children become the victims of state repression or natural calamity. Perhaps because education is always about developing to a point beyond childhood, academics, at the pinnacle of the educational profession, are especially keen to avoid appearing childish. The problem is that this can go with a general loss of wonder, a banishment of the ludic, that is at some level life-denying.

If “childhood” is problematic and definitely marginal in academic terms, far more popular as a subject of exploration, recently anyway, has been another theme that my first picture evokes: the role of memory (assumed memory) in constructing attitudes and reactions. The term “memory” groups together, in a loose alliance, commemoration, the material, textual, or ritual perpetuation of lost time, recollection, or the retrieval of the past in formal, public narratives such as professional history, journalism, guidebooks, and websites, and remembrance - the common currency of the past in everyday practices, in family traditions, and in conversation. Memory of the third kind is, as Yosef Yerushalmi pointed out in Zakhor, much older than history, and such “remembrance” also presents a serious challenge to professional history in its slipperiness, its often emotional claims to authenticity, and on the basis of that to political leverage. There is an influential strand in modern Western discussion (Cathy Caruth, Dominic LaCapra, and others) which emphasises the personal damage done by trauma and the part played by frankness and retrieval in the project of recuperation. But actually, in our part of the world, righteous indignation and the assertion of absolute claims to a certain, selfinterested view of the past are far more common.

All of this makes me unhappy with the famous arguments voiced by Hannah Arendt in her 1967 essay “Truth and Politics”. The essay brilliantly captures the fragility yet resilience of what Arendt terms “fact”, or the surviving fragments of reality through passing time. Yet when Arendt quotes with approval Montaigne’s idea that falsity is protean while truth has “only one face”, she is, I think, falling into the same trap as those who insist on a monologic claim to the rightness of their own version of the past. Her example from Clemenceau – that no-one would ever say Belgium invaded Germany – applies neatly to an age when military invasions were carried out by entire armies, as a strongly ritualised performance of power. But what of situations where illegal border-crossing is alleged, yet cannot be effectively demonstrated? Or contestations over shared territory, of the kind that take place in cultures – including most modern ones – with high levels of mobility?

Academics, particularly historians, like to concentrate on cases where “myth” can readily be undermined by “fact.” And there is good reason for this, as underlined some years ago by Roger Chartier: if all interpretations have equal value, there is no ground left upon which one may object to unscrupulous politicians. (Indeed, the argument of multiple interpretation has been extensively used by the Putin-era Russian press, for instance.) The problem is that a scrupulously argued, carefully weighed interpretation may also have limited political traction – so if political traction becomes the measure of our achievement, the result will be unavoidable stultification.

Added to that, the debunking of myth may seem more effective in a scholar’s eyes than it seems to a nonspecialist observer. Ruth Harris’s book on the Dreyfus case is pertinent here: it shows how the coherent, rational case set out by Dreyfus’s supporters, based on the scrupulous use of fact, failed because of its very detachment. In a brilliant 1967 essay on the cinema of Michelangelo Antonioni, the Russian writer Reed Grachev presents the resort to fact as a recourse of weakness – but a creative and suggestive weakness: “The pull to the factual in twentiethcentury arts is the result of a loss of confidence in the plausibility of life and a desire to use the newly retrieved facts to challenge the old criteria.” Whether we agree with this assessment or not, the emphasis that the retrieval of fact is both difficult and radical offers a more creative platform for cultural engagement than the assumption that it is always others who distort reality, and we who expose their fictions.

This does not mean accepting any old nonsense as true; as Isaiah Berlin pointed out long ago, there is a crucial difference between absolute relativism (a critical stance towards all moral and social norms) and pluralism, or the recognition of legitimate difference. But it does mean applying the mind to a careful and considered analysis of phenomena that are uncomfortable, difficult, and even foolish. For several decades, “postmodernism” has been used, rather lazily, as a term for an anything-goes preoccupation with narrative and rhetoric. But exploration of how authoritative fictions function is just as important as demonstrating that they distort reality – indeed, one might say, more important, since intelligent journalism and internet comment can be relied on for swift factual corrections. Take these two images from the recent Ukrainian crisis.

Both the pictures illustrate stories that were quickly discredited. There was no pregnant woman in the burning building in Odessa; personal items were not removed by members of the Donetsk militia from the field where MH17 met its dismal end. But both had instant impact,and a long afterlife. Of course, we can simply say that people believe what they want to believe, that truth is the first casualty of war, or blame it on the Internet as an instrument of mass credulity. But none of these explanations seem complete or even particularly interesting. Why these images?

The furtive, intimate, hurried nature of the “event Instagram” is part of it: these pictures look like the small slices of reality one is used to seeing, the genre itself reinforcing photography’s traditional link with something that has “actually happened”, according to the classic function of photography as discussed by John Berger and Susan Sontag among others. Tenniel shows us the power of one kind of fiction, of an artefact that doesn’t conceal its imaginative (its imaginary) status; the photographs demonstrate the power of an artefact that pretends simply to represent the world as it is.

Yet the photographs are not primarily documentary in force. Their blurry facture may suggest they are artless representations, but that very effect is the result of considerable work – and work that Adobe Photoshop has now made evident to, as well as realisable by, anyone. Photographs need to be processed, in the modern eye, to make them real, yet they need also to seem spontaneous – there is the paradox. These two images are perfect examples of that necessary contradiction. Added to that they act as moral mininarratives, capturing, in one shot, people so wicked that they will slaughter a pregnant woman, or comb through the belongings of the dead for self-enrichment. They pillory those represented, while attributing to the viewer a very different set of morals. They are not so different in this from the traditional images of the blood libel, which attribute to a social “other” the capacity to do unspeakable acts – while actually representing behaviour that is common enough in the culture that makes the representation. They carry a charge that it is difficult to counter: the charge of emotional truth, but their generalisations confuse the normative and the descriptive. “This should not happen” becomes “This does not happen – among us.” If soberly studied, both pictures raise pressing questions about how they were made. Who was privy to this scene? Who arrived just as a heavily pregnant woman expired, apparently without traces of blood, and managed, defying the laws of gravity, not to slip to the floor? Who was able to capture the gloating militia man as he riffled through other people’s property? Who was this trusted person who then betrayed omertà by releasing the picture to the world? The very fact that these pictures stretch ordinary reality makes them powerful – they have the omniscience of an abstract force, or perhaps even a divinity: the eye of justice, conscience, or the Lord God.

It is hard, if not impossible, to find a vulnerable place in such narratives: saying that “this did not happen” produces the response “things like this did happen” (or the accusation that one is “defending” morally repugnant behaviour). Exclamations about the stupidity of someone who might be taken in are still more problematic, as the person challenged then has a double stake in defending what they initially saw as plausible. Yes, there are many reasons for the proliferation of dubious images on the internet – the medium’s appetite for news and sensation; the slump in the political, economic, and cultural capital of investigative journalism; the shift from words to pictures in response to current events. But the material itself needs to be taken seriously, and we need to think our way into the minds of those who find it urgently engaging. Unlike real works of art, these fictions have no perceived value beyond their transmission of the values of those who created them. But they are not straightforward, and neither should our response to them be.

I am not proposing here a culturalist argument, whereby the function of analysing different languages and cultures is to crack an obscure hermeneutic code (as in Winston Churchill’s (in)famous description of Russia, “a riddle wrapped up in an enigma”). Rather, studying different languages and cultures provides a sense both of universality, of understanding without shared background and (geographical or mental) territory, and a respect for different viewpoint. The hardest thing about writing academic work in other languages is not grammar or vocabulary, but the fact that arguments are structured and expressed in different ways, and these means of expression bear directly upon the acquisition of authority by the person who does the writing. Institutional power is often not translatable across other cultures either: anyone who has run an international project will know that this can be a bruising experience, with much argument about values and strategies. But to lose the sense that you are automatically entitled to a hearing can be revealing as well as humbling. It is a source of strength, in the end, too, once you finally overcome obstacles and make your point, but realize you can only do this with due attention to perspectives that you did not originally have.

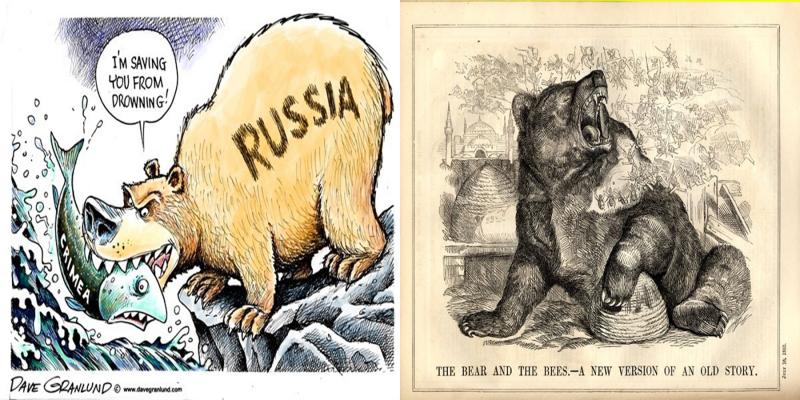

Here I am echoing Stephen Hanson’s eloquent case, in his Presidential Address last year, for the importance of regional studies. But it is one particular aspect of regional studies that I have in mind. The centrality of culture to the understanding of politics used to be taken for granted back in Cold War days. Now humanities programs are under threat, both in the US and elsewhere, as practically useless. Yet the tight links between culture and politics have not gone away. Indeed, there has been an upsurge of representations that precisely insist on the connection. For instance, the freelance cartoonist Dave Granlund’s response to the latest Crimean War is entirely in the spirit of visual gags from 160 years ago.

This might seem like a knowing in-joke on the modern cartoonist’s part, a self-conscious, smirking citation. But the assumptions of barbarism lie deep. Take this story from immediately after the MH17 was downed over Donbass:

Putin killed my son, says distraught dad

July 19 2014 at 04:50pm By Daily Mail

London - The distraught father of a brilliant maths student killed on Flight MH17 accused Vladimir Putin of his murder. Simon Mayne’s son Richard, 20, was one of ten Britons on the Malaysia Airlines jet downed by a missile in eastern Ukraine. Fighting back tears, Mr. Mayne said he had little doubt the Russian president was responsible for the loss of 298 lives. “If Putin wanted to speak out he would do so, he would sort them (the rebels) out,” said the 53-year-old teacher and company director. “Everyone knows that what is going on out there is Russian-sponsored. This is a man who rides bare-chested on a horse because he thinks people will admire him, but he’s murdered my son essentially.”

This was one of many comparable stories in the UK press the day after the MH17 tragedy. My reaction as I entered the paper-shop was nausea. Not for a minute would I wish to belittle the father’s distress, but responsible journalism should not frame a story round a desperate person’s incoherent, ill-expressed outburst of rage (“he’s murdered my son essentially”) and turn this into clickbait round the globe. Meanwhile, the Russian media displayed a comparably inadequate reaction: the father’s reaction was described by a Twitter user as “So primitive, just a propaganda,” as though “primitive” were an appropriate description of extreme grief and rage. Patriotic Russian newspapers ran allegations citing militia leader Igor’ Strelkov’s claim that the plane was full of long-dead, “putrid corpses”, when the names of those who died had already been released in Australia, a mere keyword or two away. Due legal process was enthusiastically abandoned on all sides.

The solution to this dreadful entanglement lies partly in restraint – from politicians and the press. But we, as experts, can also help. Where conflict is concerned, ignorance is most definitely not bliss. In societies where international contact is shallow-rooted and poorly informed, misunderstanding and prejudice proliferate. On the other hand, a proper grasp of language and culture help us better to understand “us” as well as “them” – our fears, our poorly rooted certainties, our unconscious arrogance. The ingrained association, in modern culture, of “the West” with civilized values creates a fertile territory for unreflective self-assertion on the part of those who inhabit the geographical territory fancifully seen as the home of ideals such as freedom and democracy. But whether we like it or not, we live in a global world, where the old binary certainties of “capitalism versus Communism” are long gone. We cannot get by on disinterred fragments of the nineteenth-century “Great Game” either, such as the automatic expectation that sovereign states will recognize their “natural” role as “buffers” or parts of an inalienable “sphere of influence”. In the push towards more sophisticated thinking, we, as experts in the region, have a central role: not just in offering informed commentary on all the areas of our subject that may be of contemporary relevance, but through insisting that all the voices in the debate are heard and properly understood – even if we do not, and should not, lend them our own authority. I am not just pleading for dialogue here; I am insisting on the absolute need for mutual understanding and conciliation. I am proud to say that we seem to have found a way toward that in our own Association over the course of the last year.

Catriona Kelly is Professor of Russian at University of Oxford (UK). Many thanks to The Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK and the John Fell Fund, University of Oxford, who provided support for study leave and travel during Professor Kelly’s term as ASEEES Board President.

Top Right: John